Article written by Pavel Ovseiko, Alison Chappell, Laurel Edmunds and Sue Ziebland – Oxford University

Health Policy Research and Systems;15(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12961-017-0177-9.

Background

All UK universities have been encouraged to take Gender Equality very seriously and instigate many different approaches to improve circumstances for women in science. It is promoted and assessed by a high profile organisation – Athena SWAN which is part of the Equity Challenge Unit (http://www.ecu.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan/). In 2011, the UK Chief Medical Officer was so dismayed at the lack of women in academic medicine, especially in leadership positions, that she sent a letter to all UK medical schools stating that their funding from the National Institute for Health Research (for their associated Biomedical Research Centres, BRCs, and funding generally) could be at risk if they had not achieved Silver award status. Not surprisingly medical schools and all scientific research establishments across the UK did a lot more to address Gender Equity, and still do.

Despite the wide-spread implementation of the Athena SWAN Charter, there has been very little qualitative evaluation of its impact.

Oxford continues to be very successful with regards to Athena SWAN and funding of the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). There is still work to be done with respect to Gender Equity here, but we have already achieved a lot; for example 16 departments of the Medical Sciences Division (MSD) also integral to the NIHR Oxford BRC, have Silver awards. All this experience of Athena SWAN in turn provided a context for us to explore the impact of these activities and policy changes, particularly as we had access to two studies that had been carried out recently in MSD that included people’s opinions about Athena SWAN.

In the early 2000s, the Athena Project and the Scientific Women’s Academic Network (SWAN) joined and evolved into the Athena SWAN Charter for Women in Science (http://www.ecu.ac.uk/equality-charters/athena-swan/). This is now an established means of advancing gender equality in the sciences here and is also being adopted by Australia and Ireland. There are criteria for each of the Bronze, Silver and Gold awards and each school, or department, applies for the appropriate level, which may or may not be awarded, and, they can be taken away again if standards fall. The key principles of the Charter are shown in the box.

Key principles of the Athena SWAN Charter for Women in Science

- We acknowledge that academia cannot reach its full potential unless it can benefit from the talents of all.

- We commit to advancing gender equality in academia, in particular, addressing the loss of women across the career pipeline and the absence of women from senior academic, professional and support roles.

- We commit to addressing unequal gender representation across academic disciplines and professional and support functions. In this we recognise disciplinary differences including: the relative underrepresentation of women in senior roles in arts, humanities, social sciences, business and law (AHSSBL), and the particularly high loss rate of women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM)We commit to tackling the gender pay gap.

- We commit to removing the obstacles faced by women, in particular, at major points of career development and progression including the transition from PhD into a sustainable academic career.

- We commit to addressing the negative consequences of using short-term contracts for the retention and progression of staff in academia, particularly women.

- We commit to tackling the discriminatory treatment often experienced by trans people.

- We acknowledge that advancing gender equality demands commitment and action from all levels of the organisation and in particular active leadership from those in senior roles.

- We commit to making and mainstreaming sustainable structural and cultural changes to advance gender equality, recognising that initiatives and actions that support individuals alone will not sufficiently advance equality.

- All individuals have identities shaped by several different factors. We commit to considering the intersection of gender and other factors wherever possible.

Samples

The two studies are very different. One was quantitative data from a validated climate survey from the US (http://www.brandeis.edu/cchange/surveys/cfsdescription/index.html) that we adapted for use in the UK (this did not ask about Athena SWAN). This was an online questionnaire that was available in May-June 2014, to approximately 4000 members of MSD. 2,407 (63%; 56% female) returned their questionnaires and 523 (22%) included anonymised comments of which 11% (42 women, 17 men) were about Athena SWAN. (Many of the other comments were similar in nature but did not mention it specifically.) The second study was qualitative, based on face-to-face interviews and took place from October 2014 – June 2015. A purposive sample of senior women scientists from MSD (n=37) and Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division (n=2) were interviewed about their careers and asked specifically about Athena SWAN as one of the questions. An aim of this study was to post their career experiences on a bespoke website (https://www.womeninscience.ox.ac.uk/).

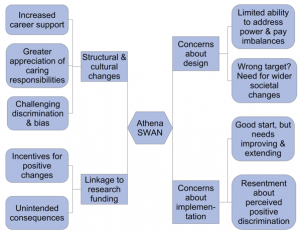

We analysed all the comments using a modified Grounded Theory approach – a relative intuitive but rigorous way of grouping the comments into themes by being organised into the framework (see the coding tree).

Results

Many of the comments about Athena SWAN were very positive, especially from the women who were interviewed. They thought there had been structural and cultural changes such as increased career support, greater awareness of caring responsibilities, and challenges to biases. However the linkage to research funding caused some to be cynical and the need for funding was driving the changes that were supporting or promoting women. Others questioned whether these changes really addressed the pay inequity or male power-bases and so cultural changes were still necessary, while some men were resentful and perceived it as positive discrimination (see the coding tree).

The coding tree

Quick sum up

Both of our data sets were collected for other purposes and so this is a secondary analysis. However, we brought together successful women scientists who were aware of/taken part in Athena SWAN activities and anonymous questionnaire responses from women and men scientists and administrators across different career stages and levels of seniority. Their views are illustrative of how Athena SWAN is perceived in a real context and can improve understanding in our university as well as being a useful contribution to the literature. On balance, implementing the Athena SWAN Charter is creating positive changes that are sustainable, however there are still improvements that can be made to Athena SWAN activities and the university culture.

Within STARBIOS2, we intend to build on this in two ways:

- We aim to repeat the interviews with women at all career stages who are associated with the NIHR Oxford BRC. BRCs have become the main academic avenue for translational medicine in the UK and so Oxford can illustrate experiences, aspirations and training needs that may be relevant to others.

- These will also inform the development of a new questionnaire which details comprehensive ‘Markers of Achievement’ capturing contributions to translational medicine in a gendered way to embed raised awareness.